Leon Czolgosz

Leon Czolgosz | |

|---|---|

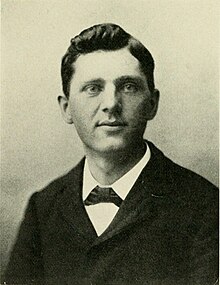

Czolgosz in 1899 | |

| Born | Leon Frank Czolgosz May 5, 1873[1] |

| Died | October 29, 1901 (aged 28) Auburn Prison, Auburn, New York, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Execution by electric chair |

| Occupation | Laborer |

| Known for | Assassination of William McKinley |

| Conviction(s) | First degree murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Signature | |

Leon Frank Czolgosz (/ˈtʃɒlɡɒʃ/ CHOL-gosh,[2] Polish: [ˈlɛɔn ˈt͡ʂɔwɡɔʂ]; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American laborer and anarchist who assassinated United States President William McKinley on September 6, 1901, in Buffalo, New York. The president died on September 14 after his wound became infected. Caught in the act, Czolgosz was tried, convicted, and executed by the State of New York seven weeks later on October 29, 1901.

Early life

[edit]Leon Frank Czolgosz was born in Detroit, Michigan,[3][4] on May 5, 1873. According to his father Paul Czolgosz, the "F" stood for Frank, and it was there because he "liked the extra initial".[5][a] He was one of eight children[7] born to the Polish-American family of Paul (Paweł) Czolgosz (1843–1944)[8] and his wife Mary (Maria) Nowak.[b] The family moved to Alpena, Michigan, in 1880. When Leon was 10 and the family was living in Posen, Michigan, Czolgosz's mother died six weeks after giving birth to his sister, Victoria.[10] In 1889, the Czolgoszes moved to Natrona, Pennsylvania, where Leon worked at a glass factory.[11] At age 17, they moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where he found employment at the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company.[12]

After the economic crash of 1893, when the mill closed for some time and tried to reduce wages, the workers went on strike. With great economic and social turmoil around him, Czolgosz found little comfort in the Catholic Church and other immigrant institutions; he sought others who shared his concerns regarding injustice. He joined a moderate working man's socialist club, the Knights of the Golden Eagle, and eventually a more radical socialist group known as the Sila Club, where he became interested in anarchism.[13][14]

Interest in anarchism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

In 1898, after witnessing a series of similar strikes, many ending in violence, and perhaps ill from a respiratory disease, Czolgosz went to live with his father, who had bought a 50-acre (20 ha) farm the year before in Warrensville, Ohio.[15][16]

Czolgosz became a recluse.[17] He was impressed after hearing a speech by the anarchist Emma Goldman, whom he met for the first time at one of her lectures in Cleveland in May 1901. After the lecture, Czolgosz approached the speakers' platform and asked her for reading recommendations. On the afternoon of July 12, 1901, he visited her at the home of Abraham Isaak, publisher of the newspaper Free Society, in Chicago and introduced himself as Fred C. Nieman (nobody),[c] but Goldman was on her way to the train station. He told her that he was disappointed in Cleveland's socialists, and Goldman quickly introduced him to anarchist friends who were at the train station.[19]

She later wrote a piece in defense of Czolgosz, which portrays him and his history in a way at odds with other sources: "Who can tell how many times this American child has gloried in the celebration of the 4th of July, or on Decoration Day, when he faithfully honored the nation's dead? Who knows but what he, too, was willing to 'fight for his country and die for her liberty'".[20]

In the weeks that followed, Czolgosz's social awkwardness, evasiveness, and blunt inquiries about secret societies around Isaak and another anarchist, Emil Schilling, resulted in the radical Free Society newspaper to issue a warning pertaining to him on September 1, reading:[6]

ATTENTION! The attention of the comrades is called to another spy. He is well dressed, of medium height, rather narrow shoulders, blond and about 25 years of age. Up to the present he has made his appearance in Chicago and Cleveland. In the former place he remained but a short time, while in Cleveland he disappeared when the comrades had confirmed themselves of his identity and were on the point of exposing him. His demeanor is of the usual sort, pretending to be greatly interested in the cause, asking for names or soliciting aid for acts of contemplated violence. If this same individual makes his appearance elsewhere the comrades are warned in advance, and can act accordingly.

— Everet Marshell, Free Society

Czolgosz believed there was a great injustice in American society, an inequality which allowed the wealthy to enrich themselves by exploiting the poor. He concluded that the reason for this was the structure of government. About this time, he learned of the assassination of a leader in Europe, King Umberto I of Italy, who had been shot dead by anarchist Gaetano Bresci on July 29, 1900. Bresci told the press that he had decided to take matters into his own hands for the sake of the common man.[21]

Assassination of President William McKinley

[edit]On August 31, 1901, Czolgosz traveled to Buffalo, New York, the site of the Pan-American Exposition, where President McKinley would be speaking. He rented a room in Nowak's Hotel at 1078 Broadway.[22]

On September 6, Czolgosz went to the exposition armed with a concealed .32-caliber Iver Johnson "Safety Automatic" revolver[23][24] he had purchased four days earlier.[25] He approached McKinley, who had been standing in a receiving line inside the Temple of Music, greeting the public for ten minutes. At 4:07 p.m., Czolgosz reached the front of the line. While McKinley extended his hand, Czolgosz slapped it aside and shot the President twice in the abdomen at point-blank range: the first bullet ricocheted off a coat button and lodged in McKinley's jacket; the other seriously wounded him in the stomach. McKinley's stomach wound was not lethal, but he died eight days later on September 14, 1901, of an infection that had spread from the wound.

James Parker, a man standing directly behind Czolgosz, struck the assassin in the neck and knocked the gun out of his hand; as McKinley slumped backward, members of the crowd began beating Czolgosz. "Go easy on him, boys", McKinley told the attackers.[26][27] The police struggled to keep the angry crowd off Czolgosz.[28] Czolgosz was taken to Buffalo's 13th Precinct house at 346 Austin Street and held in a cell until he was moved to police headquarters.

-

President McKinley greeting well-wishers at a reception in the Temple of Music minutes before he was shot September 6, 1901

-

A sketch of Czolgosz shooting McKinley

-

Site of McKinley murder marked by "x" in lower right

-

Illustration of how Czolgosz's gun was concealed. Chicago Eagle, September 14, 1901

-

Handkerchief, pistol and bullets used by Czolgosz

-

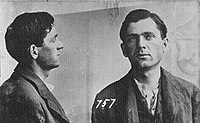

Leon Czolgosz mugshot after his arrest

-

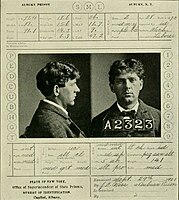

Czolgosz's prison record at Auburn State Prison

Trial and execution

[edit]

After McKinley's death, newly inaugurated President Theodore Roosevelt declared, "When compared with the suppression of anarchy, every other question sinks into insignificance."[29]

On September 13, the day before McKinley succumbed to his wounds, Czolgosz was taken from the police headquarters, which were undergoing repairs, and transferred to the Erie County Women's Penitentiary temporarily. On September 16, he was brought to the Erie County Jail to be arraigned before County Judge Emery. After the arraignment, Czolgosz was transferred to Auburn Prison.[30]

A grand jury indicted Czolgosz on September 16 with one count of first-degree murder. Throughout his incarceration, Czolgosz spoke freely with his guards, but he refused every interaction with Robert C. Titus and Loran L. Lewis, the prominent judges-turned-attorneys assigned to defend him, and with the expert psychiatrist sent to test his sanity.[31]

The case was prosecuted by the Erie County District Attorney, Thomas Penney, and assistant D.A. Frederick Haller, whose performance was described as "flawless".[d] Although Czolgosz answered that he was pleading "Guilty", presiding Judge Truman C. White overruled him and entered a "Not Guilty" plea on his behalf.[32]

Czolgosz's trial began in the state courthouse in Buffalo on September 23, 1901, nine days after McKinley died. Prosecution testimony took two days and consisted principally of the doctors who treated McKinley and various eyewitnesses to the shooting. Lewis and his co-counsel called no witnesses, which Lewis in his closing argument attributed to Czolgosz's refusal to cooperate with them. In his 27-minute address to the jury, Lewis took pains to praise McKinley.

Scott Miller, author of The President and the Assassin, notes that the closing argument was more calculated to defend the attorney's "place in the community, rather than an effort to spare his client the electric chair".[33]

Even had the jury believed the defense that Czolgosz was insane, by claiming that no sane man would have shot and killed the president in such a public and blatant manner, knowing he would be caught, there was still the legal definition of insanity to overcome. Under New York law, Czolgosz was legally insane only if he was unable to understand what he was doing. The jury was unconvinced of Czolgosz's insanity due to the directions given to them by Judge White; they voted to convict him after less than a half-hour of deliberations (a jury member later said it would have been sooner but they wanted to review the evidence before conviction).[34]

Czolgosz had two visits the night before his execution, one with two clergymen and another later in the night with his brother and brother-in-law. Even though Czolgosz refused Father Fudzinski and Father Hickey twice, Superintendent Collins permitted their visit and escorted them to his cell. The priests pleaded for 45 minutes for him to repent, but he refused and they left. His brother Waldeck and brother-in-law Frank Bandowski visited after the priests had left. His brother asked him "Who got you into this scrape?" to which Czolgosz responded "No one. Nobody had anything to do with it but me." His brother said it was unlike him and was not how he was raised. When asked by his brother if he wanted the priests to come back, Czolgosz said, "No, damn them. Don't send them here again. I don't want them," and "Don't you have any praying over me when I am dead. I don't want it. I don't want any of their damned religion." His father wrote a letter to his son the night before his execution, wishing him luck and informing him that he could no longer help him, and Leon had to "pay the price for his actions."[35] Although after the trial Czolgosz and his attorneys were informed of his right to appeal the sentence, they chose not to after Czolgosz declined. Also, the attorneys knew that there were no grounds for appeal; the trial had been "quick, swift, and fair."[36]

Czolgosz's last words were: "I killed the President because he was the enemy of the good people – the good working people. I am not sorry for my crime. I am sorry I could not see my father."[37] Czolgosz was electrocuted by three jolts, each of 1,800 volts, in Auburn Prison on October 29, 1901, forty-five days after McKinley's death. He was pronounced dead at 7:14 a.m.[38] The state electrician (executioner) of Czolgosz was Edwin Davis.[39]

Waldeck Czolgosz and Frank Bandowski attended the execution. When Waldeck asked the warden for his brother's body, to be taken for proper burial, he was informed that he "would never be able to take it away", and that crowds of people would mob him.

Czolgosz was autopsied by John E. Gerin;[e] his brain was autopsied by Edward Anthony Spitzka. The autopsy showed his teeth were normal but in poor condition; likewise the external genitals were normal, although scars were present, the result of chancroids. The autopsy showed the deceased was in good health; a death mask was made of his face.[37] The body was buried on prison grounds. Prison authorities had planned to inter the body with quicklime to hasten its decomposition, but decided otherwise after testing quicklime on a sample of meat. After determining that they were not legally limited to the use of quicklime for the process, they poured sulfuric acid into Czolgosz's coffin so that his body would be completely disfigured.[40] The warden estimated that the acid caused the body to disintegrate within 12 hours.[38] His clothes and possessions were burned in the prison incinerator to discourage exhibitions of his life.[41]

Legacy

[edit]Emma Goldman was arrested on suspicion of being involved in the assassination, but was released due to insufficient evidence. She later incurred a great deal of negative publicity when she published "The Tragedy at Buffalo". In the article, she compared Czolgosz to Marcus Junius Brutus, the assassin of Julius Caesar, and called McKinley the "president of the money kings and trust magnates."[42] Other anarchists and radicals were unwilling to support Goldman's effort to aid Czolgosz, believing that he had harmed the movement.[43]

The scene of the crime, the Temple of Music, was demolished in November 1901, along with the rest of the Exposition's temporary structures. A stone marker in the median of Fordham Drive, now a residential street in Buffalo, marks the approximate spot (42°56.321′N 78°52.416′W / 42.938683°N 78.873600°W[44]) where the shooting occurred. Czolgosz's revolver is on display in the Pan-American Exposition exhibit at the Buffalo History Museum in Buffalo.

After Czolgosz's death, Lloyd Vernon Briggs (1863–1941), a Boston alienist who later became the Director of the Massachusetts Department for Mental Hygiene, reviewed the Czolgosz case in 1901 on behalf of psychiatrist Walter Channing (1849–1921),[45] concluding Czolgosz was insane; that conclusion has since been challenged.[46]

Czolgosz is buried at Soule Cemetery in Cayuga County, New York. His grave is unmarked, with a stone reading, "Fort Hill Remains".[47]

Portrayals in media

[edit]- Czolgosz's execution was portrayed in the 1901 silent film Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison.

- He is featured as a central character of Stephen Sondheim's musical Assassins. His assassination of McKinley takes place during a musical number called "The Ballad of Czolgosz".

- He was portrayed in the Reaper episode "Leon" by Patton Oswalt, as an escaped/captured/released/re-captured soul from Hell who could turn his arms into large guns, but had issues with his father.

- In season 7, episode 15, of the CBC television drama series Murdoch Mysteries, "The Spy Who Came Up to the Cold" (2014), Leon Czolgosz is portrayed by Goran Stjepanovic.

See also

[edit]- John Wilkes Booth, assassin of President Abraham Lincoln

- Charles J. Guiteau, assassin of President James A. Garfield

- Lee Harvey Oswald, assassin of President John F. Kennedy

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ His three older brothers, Waldeck, Frank and Joseph, were born in Poland while Leon was the first child born in Michigan.[6]

- ^ Czolgosz's ancestors probably came from what is now Belarus. His father may have immigrated to the US in the 1860s from Astravyets (Ostrowiec) near Wilno. When he arrived in the United States, he gave his ethnicity as Hungarian and changed the spelling of his surname from Zholhus (Жолгусь, Żołguś) to Czolgosz.[9]

- ^ Czolgosz also sometimes used the surname "Nieman" ["Nobody"] and variations thereof[18]

- ^ Dr. McDonald's description of the trial.

- ^ Everett 1901, p. 448. "The physicians were: Dr. Carlos F. MacDonald of New York and Dr. Gerin of Auburn. Other witnesses were: E. Bonesteel, Troy; W. D. Wolff, Rochester; C. F. Rattigan, Auburn; George R. Peck, Auburn, N.Y.; W. N. Thayer, former warden of Dannemora prison, who assisted Warden Mead, and three newspaper correspondents."

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Twelfth Census of the United States, United States census, 1900; Orange, Cuyahoga, Ohio; roll T623 1261, page 4A, line 34.

- ^ "Czolgosz, Leon F.". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Columbia University Press. 2000. Retrieved August 24, 2022 – via encyclopedia.com.

- ^ "Leon Frank Czolgosz Biography". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ^ Briggs 1921, p. 262; Everett 1901, p. 73.

- ^ Federman, Cary (2017). The Assassination of William McKinley: Anarchism, Insanity, and the Birth of the Social Sciences. Lexington Books. ISBN 9781498565516.

- ^ a b Everett 1901, Chapter 5

- ^ Channing 1902.

- ^ Rauchway 2004, pp. 114, 126.

- ^ Андрей Довнар-Запольский (November 27, 2008). "Президента США Уильяма МакКинли застрелил белорус?". Kp.ru. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Miller 2011, pp. 41.

- ^ Briggs 1921, p. 287; Rauchway 2004, p. 115.

- ^ Miller 2011, pp. 56.

- ^ Miller 2011, pp. 57–60.

- ^ Jensen, Richard Bach (2013). The Battle against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-65669-7.

- ^ Miller 2011, p. 231.

- ^ "Assassin Known..." & September 8, 1901, col. 1 para. 8.

- ^ Berlinski, Claire (2007). Menace in Europe: Why the Continent's Crisis Is America's, Too. New York City: Three Rivers Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4000-9770-8.

- ^ Vowell, Sarah (2005). Assassination Vacation. New York City: Simon and Schuster. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-7432-8253-6.

Fired, then blacklisted, he got his old job back by working under the alias Fred Nieman. German for 'nobody,' Nieman is the name Czolgosz first gave to the Buffalo police upon arrest.

- ^ Goldman 1931, pp. 289–290.

- ^ "The Tragedy at Buffalo".

- ^ Sekulow, Jay Alan (2007). Witnessing Their Faith: Religious Influence on Supreme Court Justices and Their Opinions. Sheed & Ward. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4616-7543-3.

- ^ "Czolgosz Says He Had No Aid". Chicago Sunday Tribune. September 8, 1901 – via mckinleydeath.com.

- ^ Taylerson, A. W. F. (1971). The Revolver, 1889–1914. New York City: Crown Publishers. p. 60.

- ^ Johns, A. Wesley (1970). The Man Who Shot Mckinley. South Brunswick N.J.: A. S. Barnes. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-498-07521-6.

- ^ Leon Czolgosz and the Trial – "Lights out in the City of Light" – Anarchy and Assassination at the Pan-American Exposition Archived February 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Legal Aftermath of the Assassination of William McKinley – Pan-American Exposition of 1901 – University at Buffalo Libraries". buffalo.edu. March 30, 2024.

- ^ "September 6, 1901". nps.gov.

- ^ "The Trial and Execution of Leon Czolgosz". Buffalohistoryworks.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Doherty 2011.

- ^ Briggs 1921, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Oliver, Willard M.; Marion, Nancy E. (2010). Killing the President: Assassinations, Attempts, and Rumored Attempts on U.S. Commanders-in-Chief: Assassinations, Attempts, and Rumored Attempts on U.S. Commanders-in-Chief. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-313-36475-4.

- ^ Hamilton, Dr. Allan McLane. Autobiography. Pre-1921

- ^ Miller 2011, p. 325.

- ^ Great American Trials 1994, pp. 225–227.

- ^ "Assassin Czolgosz Pays Death Penalty in Electric Chair". San Francisco. The San Francisco Call. p. 1.

- ^ Briggs 1921, p. 260.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Carlos F. (January 1902). "The Trial, Execution, Autopsy and Mental Status of Leon F. Czolgosz, Alias Fred Nieman, the Assassin of President McKinley" (PDF). The American Journal of Insanity. 58 (3): 375. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Execution of Leon Czolgosz – 'Lights Out in the City of Light' – Anarchy and Assassination at the Pan-American Exposition". Ublib.buffalo.edu. June 11, 2004. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Banner, Stuart (2003). The Death Penalty: An American History. Harvard University Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 0-674-01083-3.

- ^ "Assassin Czolgosz..." & October 30, 1901.

- ^ Brandon, Craig (2016). The Electric Chair: An Unnatural American History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-7864-5101-2.

- ^ "The Tragedy at Buffalo". Ublib.buffalo.edu. June 11, 2004. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Goldman 1931, pp. 311–319.

- ^ "Site of the Assassination of President McKinley". Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Rauchway 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Richardson, Heather Cox (August 24, 2003). "A captivating tale of a murder that mattered, and why it did". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Kirst, Sean (December 21, 2016). "100 bodies buried in a backyard: Is one a Medal of Honor recipient?". The Buffalo News. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

Cited sources

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

- "Assassin Czolgosz Is Executed At Auburn. He Declared that He Felt No Regret for His Crime. Autopsy Disclosed No. Mental Abnormalities. Body Buried in Acid in the Prison Cemetery". The New York Times. October 30, 1901. p. 5. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

At 7:12:30 o'clock this morning, Leon Frans Czolgosz, murderer of ... the formal finding in his case was composed as follows: Foreman, John P. Jaeckel. ...

- "Assassin Known As A Rabid Anarchist; Parents of Czolgosz Found at Home in Cleveland. One Member of the Family Now Draws a Pension from the Federal Government". The New York Times (published September 8, 1901). September 7, 1901. p. 4. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- Briggs, L. Vernon (1921). "Part II: Czolgosz". The Manner of Man That Kills. Boston: Richard G. Badger. pp. 231–344. OCLC 1047670272.

- Channing, Walter (1902). "The Mental Status of Czolgosz". American Journal of Insanity. 59 (2): 1–47. doi:10.1176/ajp.59.2.233. ISSN 0002-953X.

- Doherty, Brian (January 2011). "The First War on Terror". Reason Magazine. ISSN 0048-6906. Retrieved June 22, 2011. a review of The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists, and Secret Agents, by Alex Butterworth, Pantheon Books.

- Everett, Marshall (1901). Complete Life of William McKinley and Story of his Assassination. Historical Press.

- Goldman, Emma (1931). Living My Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- "Leon Czolgosz Trial: 1901". Great American Trials. New England Publishing. 1994. pp. 225–227.

- Miller, Scott (2011). The President and the Assassin. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6752-7.

- Rauchway, Eric (2004). Murdering McKinley: The Making of Theodore Roosevelt's America (paperback ed.). Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-1638-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Carnes, Mark C. (1999). "Czolgosz, Leon F. (1873–1901), assassin of President William McKinley". In Garraty, John A.; Carnes, Mark C. (eds.). American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0500973. ISBN 0-19-520635-5.

External links

[edit]- Leon Czolgosz Signed Confession to the Assassination of President McKinley Archived December 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Film: Execution of Czolgosz, with panorama of Auburn Prison (1901 reenactment), Library of Congress archives

- PBS biography of Czolgosz

- Leon Czolgosz – Mr. "Nobody": Original Letter Archived December 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- 1873 births

- 1901 deaths

- 1901 murders in the United States

- 20th-century executions by New York (state)

- 20th-century executions of American people

- American anarchists

- American male criminals

- American people of Belarusian descent

- American people of Polish descent

- Anarchist assassins

- Assassination of William McKinley

- Assassins of presidents of the United States

- Executed American assassins

- Executed anarchists

- Executed people from Michigan

- History of Buffalo, New York

- History of Cleveland

- Illegalists

- People convicted of murder by New York (state)

- People executed by New York (state) by electric chair

- People from Alpena, Michigan